The Soviet Union, the "Tartars," and Wayne State University

In 1927, Joseph Stalin's power within the Soviet Union had begun to consolidate. Since the previous charismatic leader Vladimir Lenin's decline in health and ultimate death, the nation and its allies had struggled. The economy was in rapid decline, falling well behind the Western nations their leaders promised to surpass. Stalin utilized these difficult times to turn the blame on his political enemies, succeeding in purging many bureaucrats, intellectuals, and religious groups.

During that same year, on the other side of the political spectrum and globe, the College of the City of Detroit held a student poll. The subject was to decide on the mascot for the newly emerging athletic teams. Among various options such as the Dynamics, the Pioneers, or the Dragons, the students chose the name "Tartar." After the school change its name to Wayne University in 1934 and became a state school in 1956, its athletic teams became known as the "Wayne State Tartars." It wasn't until 1999 that the Wayne State University mascot was changed to the now known name of the "Warriors."

Of course, this chronological connection is no more than a coincidence. Yet what unfolds surrounding the Soviet Union, the "Tartars," and Wayne State University's use of the name illustrates a telling story that allows us to explore some questions regarding representation and socio-political awareness.

Let's begin with the question: who are the Tartars?

The devil is in the details.

The "Tartars" are a creation of psychological warfare from the 13th~14th century by the terrifically terrifying Mongolian Empire. On the other hand, the "Tatars" (without a crucial r in the middle) are Turkic-speaking people that played a central role in the expansion of the Mongolian Empire, the Silk Road, and now span across various nations from Eastern Europe well into Central Asia.

These two names have caused much confusion, even the often credible encyclopedic source Britannica suggests that the two can be used interchangeably. Although we can not say conclusively, the mix-up between the two names is due to the ignorance of foreigners, rather than any historical accuracies. Allow me to break it down further.

The Mongols and the Tartars

It is well acknowledged that the vast Mongolian Empire was the largest land empire in world history. Their influence spanned from the Sea of Japan all the way to Eastern Europe at the height of its power, and as illustrated by anthropologist Jack Weatherford, played a significant role in creating the modern world. The empire promulgated knowledge, skills, and technology from previously unknown parts of the world to the other. It is truly baffling how much larger and more complex the Mongolian Empire made the world in just a century or so.

However, notwithstanding the much praise people attribute to the Mongols and their ultimate leader Ghengis Khan, they were also brutal. It is difficult to conclusively assess how many lives perished, but estimates guess at around 40 million people. To help imagine the impact such killings had, one study offers a unique insight.

A paper published in the journal Holocene suggested that the drastic decrease in world population during the Mongol expansion was large enough to lower the level of CO2 in the atmosphere of the globe. Similar effects are seen in the Black Death (1350ish~1400ish) and the conquest of the New World. Now, just imagine the terror that such mass killings would have caused in a world where knowledge and news spread much slower than rumors.

But how did the Mongols conquer the world?

The Mongols never had the largest armies or the most sophisticated technologies for much of their reign. Historians largely attribute the success of Ghengis Khan's army to savvy political alliances, brilliant tactical maneuvering, and most importantly for the spread of the word "Tartars," psychological warfare.

The Mongols would surround cities for days, catapult humans on fire into cities to incite chaos, and would intentionally spread horrific rumors of utter destruction they would bring unless the targetted people surrendered. This is where the name "Tartar" may have left its deepest roots.

Through merchants, dogmatic preachers, and other travelers, the word of Mongolian terror spread. Mixed in with the real stories of destruction were fantastical tales of the devilish people that roamed freely across the Eurasian steppe. And as the Mongolians pushed further west into Europe, they continued to spread rumors about the fear they would bring unless people surrendered to their authority without question.

Among such stories, the name "Tartar" was used and invoked much fear, as it quite literally entailed that they were people from hell. This word is derived from the Greek/Latin term "Tartarus" which means the underworld or more simply, hell.

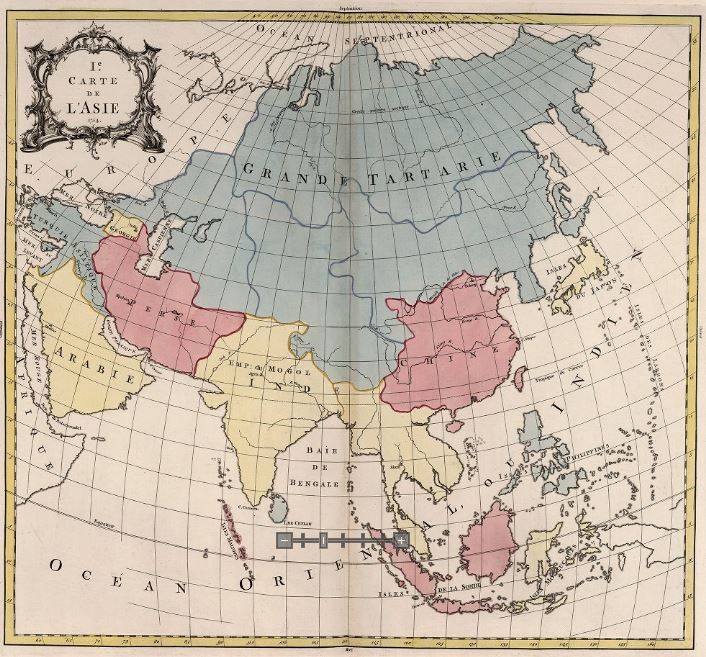

Soon, the name "Tartar" was used to label all peoples to the east of Europe, where some early cartographers labeled most of the Asian continent as "Tartary," or "Land of the Underworld."

Now, this is where things get confusing. Because a distinct group of nomadic people used the word "Tatar" to refer to themselves from as early as the 5th century, and were later incorporated into the grand empire known to Europeans as the "Tartars." The Tatars were a greatly successful people and ended up becoming a large part of the Mongolian Empire's population.

However, as the diverse peoples within the Mongolian Empire began to gain more autonomy as the empire collapsed, the "Tatars" became almost synonymous with "Tartars" due to the various overlaps in their name and history.

For centuries that follow, many documents show that the words "Tatars," "Tartars," and "Mongols" were used interchangeably; almost always referring to brutal, "bestial," and backward people living to the east of Europe (Giffney 2012).

Such images of fear invoking people were soon taken up as mascots, characters, and metaphors. Notable among them was Wayne State University.

The book that chronicles the history of Wayne State University, A Place of Light: The History of Wayne State University, written by Leslie Hanawalt in 1967, notes:

"From 300 suggestions [for the name of the athletic teams]...the athletic board picked a Mongol tribal name, "the Tartars," to signify fighting ability and also the dismay of opponents who, as happened often, underrated a City College team and found they had caught a Tartar" (Hanawalt 1967, 189).

This single statement indicates that the school, like countless others across the English-speaking world then, did not fully grasp the difference between Tartar, Tatar, and Mongol.

"Tartar" is not a tribal name for the Mongols, but rather a European interpretation of the fear these people invoked. If they wished to use a tribal name within the Mongol empire (I can only imagine they were thinking of the ferocity of the Mongolian empire and not the people in general), "Tatar" would be more accurate. Again, we see the confusion between the three terms.

Regardless, the ignorance of other people's history and sociopolitical situation goes beyond just not knowing the difference between these names and peoples. It is because during the years Wayne State University used the word "Tartar" to simply show how good they could be in athletic competitions, the "Tatars" were being accused of crimes they did not commit, forced into labor camps, and deported en masse from their homes.

Stalin and the Tatars of Crimea

Beginning in 1944, Joseph Stalin began to accuse Tatars living in Crimea of collaborating with the German Nazi government during World War 2. Close to 200,000 of these Crimean Tatars were deported, mainly to Central Asia. Life deteriorated rapidly ever since.

Countless people passed away due to the inhospitable means of deportation, malnutrition, and poor resettlement planning. The lack of food, poor adjustment to the new climate (which was quite harsh compared to Crimea), and the extreme control they were put under lived up to the horrors of the Soviet Union that we read of in history textbooks.

Although documentation is sparse and largely difficult to account for, estimates show that approximately 18% of the deportees passed away between 1944 and 1952 (Some estimates go as high as 50%). Moreover, about 80% of all deportees were women and children, as many of the men were sent to the horrific Soviet labor camps or were already serving in the Red Army (Pohl 2010).

During this same period, a process of "detatarization" began on the Crimean peninsula. In short, any remnants of the Indigenous population were to be removed and destroyed. Books, statues, monuments, and more were all replaced, while Russian and Ukrainian families moved into the now-empty homes of the Crimean Tatars.

The exile and oppression continued even throughout the "de-Stalinization" period after Stalin's death and well into the 1990s. Finally, as the powers of the Soviet Union began to disintegrate, did some Tatars return to their homeland.

Note: Of course, Tatars did not live solely in Crimea. Various Tatar groups live across Eastern Europe well into Siberia and Central Asia.

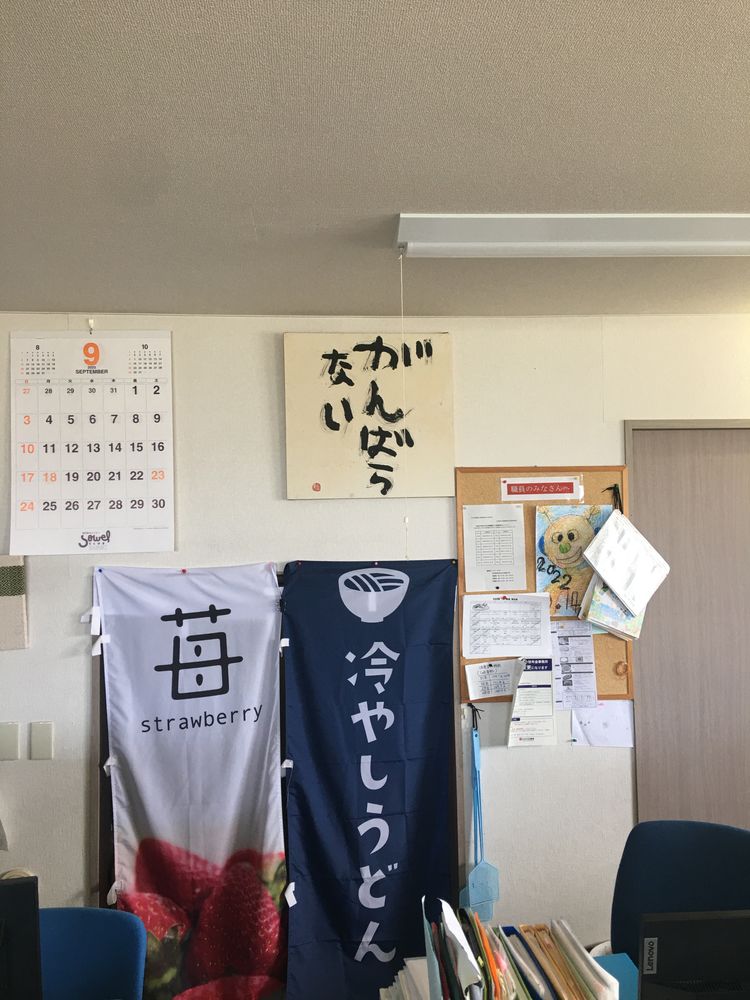

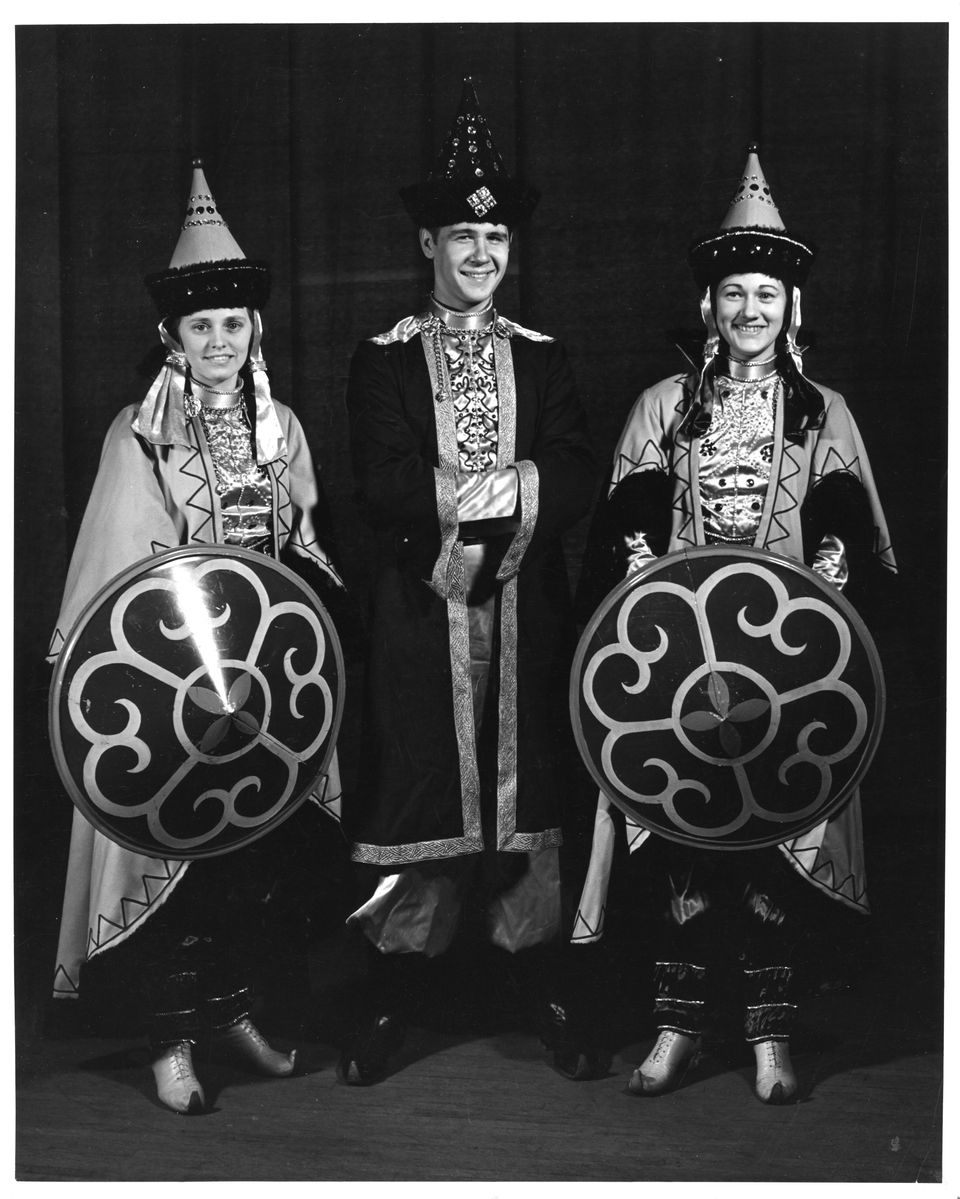

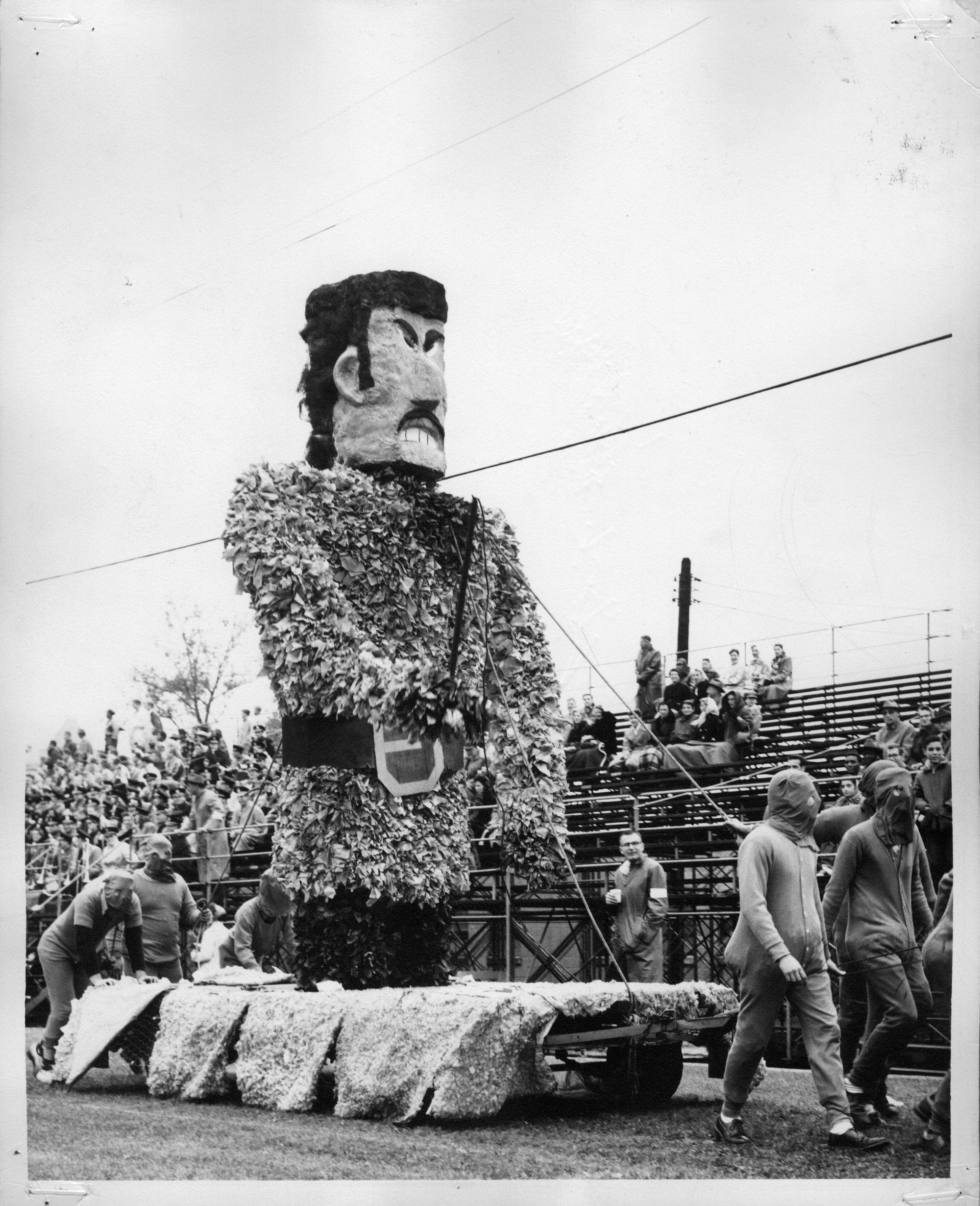

Wayne State University's Tartar

Throughout this entire period, Wayne State University continued to use the term "Tartar" for their athletic teams. They created mascot floats to pull through parades, wooden carvings, and drew shirtless "Tartars" to serve as the school logo.

The confusion on what exactly they meant by "Tartar" is evident.

Some of these depictions show the stereotypical and racist depiction of Chinese/East Asian men: a pointed hat, slit eyes, fu manchu, and bucked teeth.

Others incorporated stereotypes (again, racist) of people from the Middle East, with turban-esque hats and curved swords.

And the shirtless "Tartar" that somehow made it as the official school mascot, is the ultimate depiction of the lack of understanding many had towards what exactly they were trying to represent with the word "Tartar."

As most groups labeled as "Tartar" live in cold and even sub-arctic climates, being shirtless would no doubt be the last thing many would choose to do. Even the simple fact that the illustrator chose a sword over the bow is another indication of the pure imaginative reality they had of their beloved "Tartar."

More ironic is that in this same period that the "Tatars" were suffering in the Soviet Union due to ethnic and racial discrimination, Wayne State University's campus served as one of the crucial spaces for anti-racist discourse that culminated into the Civil Rights Movement (Boyd 2017). As the Civil Rights Movement also gained international momentum, it would not have been difficult to see the struggles the Tatars faced, or even to attempt to learn who exactly the school was used as their mascot.

Note: I have not received any comments regarding my numerous inquiries into this from the school.

To End

But the question remains: so what? Is this "coincidence" really problematic? Or are we just problematizing and judging the past based on our current values?

Maybe.

Yet what needs to be explicitly stated is that logos and mascots can become a powerful trope in the grand narrative of our interconnected world. Especially if these logos and mascots refer to real people, real histories, and are used without reflection.

Such concepts can be expanded beyond just logos and mascots, but even to the recent calls for "representation" in many formerly (or currently) racist and xenophobic media outlets, such as Disney or Marvel. Why should people want to be represented by those who have time and time again misrepresented and perpetrated a racist stereotype for years? Do we simply forgive them if they do a good job now, continuing their monopoly of media, entertainment, and more?

Allow me to end with a classic quote from Dr. Edward Said's book Orientalism:

"From the beginning of Western speculation about the Orient, the one thing the Orient could not do was to represent itself. Evidence of the Orient was credible only after it had passed through and been made firm by the refining fire of the Orientalist’s work."

![[Guest Post] Exploring Colonial History through Art](/content/images/size/w750/2023/11/graphite-island-banner.png)